I always like to keep this column current as you know so I shall quote from the 18th century poet and writer Alexander Pope. You’ve probably heard several of his popular quips, maybe even quoted them as they are in common usage, without appreciating the author. But four hundred years ago he was a product of the Enlightenment, a period when thinking people had escaped from the old ideas of science when previously books were only written in Latin, and religion dictated the limits of knowledge. New ideas were spreading, not only in how an individual could follow his faith, but in the arts, mathematics, medicine, astronomy and all areas where thinking minds could explore new possibilities.

Most of these ideas were spread, not just by word of mouth, but by the previous invention of the printing press, which not only reproduced them, but allowed them to be shared and translated into other languages to stimulate like minded scholars across the known world. So the expansion of knowledge was what we now call exponential - a sort of historic Moore’s Law.

Several of Pope’s observations are as familiar as the first line of a song - Fools rush in…Hope springs eternal, etc - but one that has stood the test of time is, A Little Learning is a Dangerous Thing.

At first glance this may seem a curious comment when the thirst for knowledge was the new obsession but actually it contains that note of caution that a mere superficial study of facts can be deceptive. Pope is not saying don’t bother to learn anything, but be careful what you think you know. In many ways this is a more eloquent way if expressing what the bumbling American politician Donald -not the Trump - Rumsfeld tried to explain when he fumbled ‘there are things that we don’t know we don’t know’.

Sometimes there is wisdom in ignorance, and Pope’s warning to education is as relevant today in 2024 as it was in 1724. The more we know about everything from the secrets of the smallest atom to the vast expanse of the universe, the more we realise how much more we have to learn, and being aware of that conundrum is the antidote to any idea that we have reached some sort of pinnacle in the development of human intelligence.

If you have spotted the direction this column is heading in then it proves that this is both written, and read, by a human being, because we are still unique in being able to make that quantum leap to recognise things that aren’t immediately obvious. The idea that we can give up on learning and simply rely on computers to do all the tedious accumulation of knowledge is fatally floored, even if it is acquiring popular support.

Several great minds smarter than me have pointed out that using the word intelligence to describe an artificial creation of wisdom is incorrect. Its origin is the Latin ‘intelligere’ which also implies a journey, an exploration in which new things are discovered rather than old things already known about. How many people of a certain generation can only find their way by Google maps, rather than by remembering landmarks like a favourite tree or church? Would they even know the church was there? Ask a random passerby the directions by a single road name or location and see what I mean.

I have often pointed out that using a computer you only find the things it thinks you are looking for, rather than other things that might be relevant. Even if it makes suggestions they are for its benefit, not yours, in order to collect more information about your preferences and behaviour. It might seem fanciful to point out that Christopher Columbus only stumbled upon the American continent because he was actually looking for China, but you do wonder whether in some alternative universe the computer was invented before the printing press, it would still be advising you that the world was flat. It seems ironic that when we have never had so much access to available knowledge, we are increasingly limiting ourselves in its selection in real terms.

As always, my inspiration for this monthly rant comes mostly from customers as meeting and dealing with ordinary people over the counter, and trying to balance their needs and expectations is a great reality check to any ideas of intellectual progress, and technical understanding. This is in complete contrast to the suggestion by Adobe in particular that their advances in AI mean that the average person, with no technical training or aptitude, can tackle exceptional tasks. What shocks me is that far from coping with difficult ones, they seem unable to deal with simple ones.

You might expect older generations to struggle with new technology, but we have come a long way

In the digital age that those who struggled through the early days of hopelessly underpowered home PCs, internet connectivity via painfully slow and often interrupted modems, seem far more able to adapt. Perhaps they have learnt that very human skill of problem solving without having to ask an electronic expert for a solution. And most importantly, in doing so, probably learned a little something else - perhaps not a big something - but one of those incremental pieces of a jigsaw that adds to the wealth of human knowledge.

So what has this got to do with Digital Imaging? It’s the never ending learning curve - just when you think you’ve ‘smashed it’ to quote my young friends, you find you are the one in pieces. As an old photographer, I had the difficult transition, after several decades of understanding film, of getting my head around a totally new form of image capture. The fact that cameras and lenses looked familiar was an illusion, the technology was totally alien at the time.

I often have to remind students who are excited by the novelty of film, that not knowing what was going to come out was not an excuse. You had to understand how the emulsion would react to light, and how to adjust the camera controls to help it. Digital is the same but different in that working out how pixels, and their electronic nerve centres behave when illuminated is crucial. If you are simply going to press a button and hope the processor will do all the difficult stuff then you are achieving very little, especially when you can’t work out why your pictures are so awful.

Printing was a massive help to my digital education, much like processing film in the darkroom, you learn to balance lightness and darkness together with the mid-tones and shadows. You also learn that colour can be really temperamentally and not at all what we see with our eyes. Photoshop still uses the same titles to many of its basic actions, even colour temperature, though many new to modern photography may not appreciate the essential relationship between them. But even back then my printing was limited to the home enlarger and the hand finished print. Anything more commercial, in quantity or screened for publication, was left to the specialist so I never had to worry about dots per inch or CMYK. Now I have to be an expert in it all - or at least I will be when I stop learning!

Back in the days when this column started we had barely completed the move from analogue printers to digital, and I think we thought it would be a brief series of how to adjust images for print much like adding a bit of density or single colour on the glass. But twenty years on the challenge has become so very much more complicated, as has trying to explain it. As much as I try and simplify advice, and make how-to tips as straightforward as possible, it seems to get more difficult as there are many more options available. Some things that to me are almost instinctive - due to experience -are far more complicated to anyone trying to tackle them for the first time.

It’s not just in digital printing of course, but across the board, in almost everything we do and everything we use in our daily lives there has been a trend to make things more ‘user friendly’ which also translates into being easier to sell to the innocent, as well as probably cheaper to produce as it doesn’t have any inconvenient and expensive features. Exploiting people’s natural impatience is a great marketing tool, but also increases the pressure of expectation - in what can be done, when it can be done and for what price. Next time a customer tells you they are going to buy a printer to save time and money just smile politely and wish them well. Try not to fall out with them as you will very likely see them again sometime!

So we come back full circle to Adobe and their very wonderful products. Don’t think this is sarcasm, they are truly amazing, and having been part of the digital journey these past decades I can very much appreciate the technical achievements they represent. The difference between the first model of Photoshop and the very latest is as much as that between a Model T Ford (younger readers might have to Google that) and a Tesla. But to suggest as a promotional statement that no previous knowledge is needed is as ludicrous as dropping the driver from one to another. Yeah I know the steering wheel still turns in the same direction, but Musk’s next creation probably won’t even have one to avoid confusing the owner.

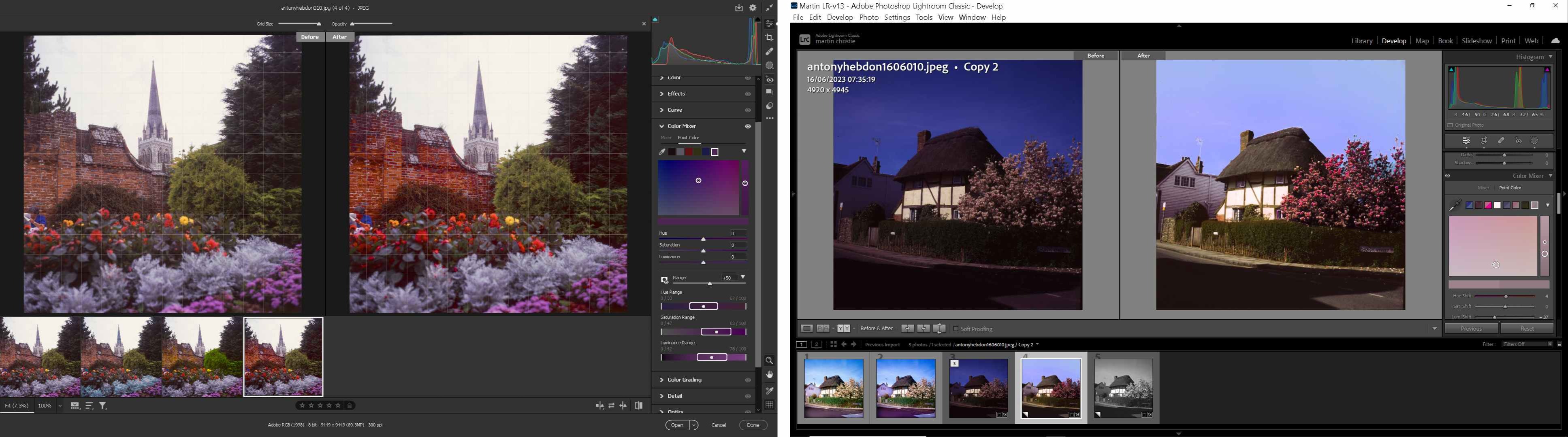

Although I have In Design and Illustrator as part of the package on my computer I hardly ever use them, as I find I have to spend time working out how to use them, or at least remembering how I used to use them. I use Photoshop and Lightroom almost exclusively, although I don’t often mention the latter here as it would take too long to explain unless, like me, you’ve been a guinea pig for Adobe from the early days and adopted all the tricks. Even then swapping from one to another isn’t as ‘seamless’ as the creators would have you believe.

There are some things, particularly editing and selecting multiple files, that are much easier done in Lightroom than ponderously handled in Photoshop. But that’s only because I know LR intimately, and am aware of all its idiosyncrasies. I sometimes have to bite my tongue and resist telling a work colleague ‘you want to do it like this’ when I realise I need to take half an hour to supervise the job.

That’s not because they are stupid, but because the software is complicated, and no job is ever simple.

Unlike all of the examples of smart advice you can get in tutorials, we don’t have the advantage of selecting jobs we want to work on. We have to sort out what we get. In doing so we do have a fantastic range of tools available - the best ever - but if you only have a basic understanding of how to use them, or even which ones to use, you have a mountain to climb - with or without a Google map!

martin@colourfast.co.uk

.jpg)

.png)