The story so far. In the beginning there was paint. You could dab a symbolic brush into a sympathetic colour and use it to spread the same hue to fill in the gaps and expand an image to fit the space needed to print it. But other than that there was very little option to change the shape and size other than cropping or stretching, or even pasting in something extra. I mention this by way of introduction to those who only know the digital world because before it, when we worked with real hard copy prints, we didn’t even have that option. We would intentionally choose originals that had extra space and margin that could be used to fill the expected void. As a photographer shooting for a magazine I would try to include an extra bit of sky that could hold a headline, or ground below that could host a caption.

There was some pre-print editing that could be done in the darkroom, some of it very creative and indeed the tricks of dodge and burn with the light source are recognised by the use of those terms in current software. And there was post print manipulation before Photoshop by liberal use of the airbrush to remove unwanted spots or even disgraced politicians to perfect an image. But this was all time consuming and the work of the specialist and therefore costly.

What digital photography created was the pixel - the basic building block of an electronic image. And it was quickly realised that you could copy that pixel and put a clone somewhere else. And so it began. And while it may look like a crude action now, it is only a short leap in technology to the intelligent use of machine learning and memory we now take for granted. We can no longer just copy, but recreate and reimagine originals to an extent that was not only impossible before but almost unimaginable.

I introduce imagination for a reason because it’s a very particular human creation, coming from some deep corner of the mind, and sparked by a complex series of senses, sights and memories, often completely unpredictable. As such it is almost exactly the opposite of machine learning - at least at the current stage of artificial intelligence. It’s important to appreciate this despite the fact it may magic up apparently unexpected results. There is always, however obscure, a logical path behind them. If you can get your head around that then you will begin to understand exactly why AI works, and also why, sometimes, it also doesn’t.

It is an incredible tool, but it is, despite all the hype surrounding it, an instrument and not a magic bullet. It still needs guidance to point it in the right direction or it will produce the sort of random effects caused by a computer desperately trying to search for some sensible solution to a problem which to it looks like chaos. As humans we can take that creative leap to join up the dots because we know where we want to end up. The electronic brain is desperately trying to juggle dozens of options without ever knowing which is the best - until we decide for it. In theory it learns based on our choices, but if every task is different, it’s a very steep learning curve even for a computer.

Of course in the print business we are more concerned with the practical application of AI rather than producing fantasy landscapes and figures. It’s more about altering backgrounds and subjects to suit size and content than conjuring up dungeons and dragons. Whether it is simply adding bleed to extend the boundaries of an image, or altering its dimensions to fit, the problems have always been with us since the print bureau ceased to create original work and welcome the varied offerings of customers own self generated files.

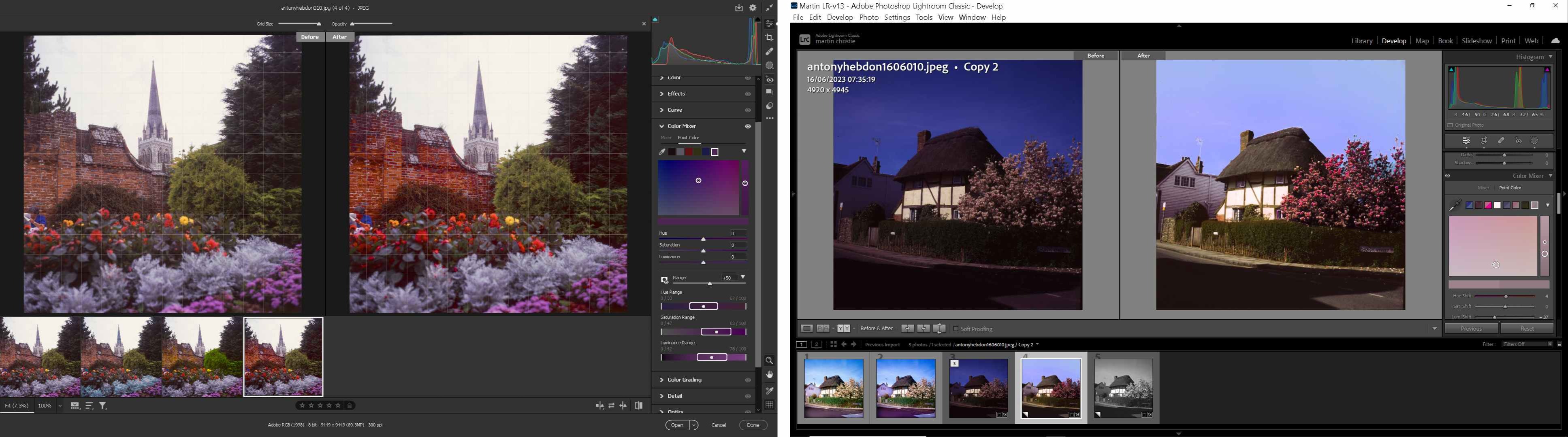

For some years we have had content aware, which works pretty well for simple filling of similar items, and has a manual override to give a degree of control. It’s actually quite a good guide to how further developments in intelligent editing work. People who regularly do crosswords get to know the mind of the creator and therefore tend to anticipate some of the more subtle information disguised in the clues. The more you use content aware, you spot the things that may distract it from what you want it to do, and learn to avoid giving it too much of a challenge all at once. Small selected increments are better than big chunks, and more precise selection will save you time in the end. Always remember that if you end up with a few bits of unwanted debris, as long as you keep the marching ants active you can still use the old faithful clone tool to touch up. Even the basic fill tool still has a place - it doesn’t have to be all high tech just because you have it available if something else will do a better job, and faster.

Of course only experience and familiarity with the tools can teach you that, but it’s a cautionary note to remember that there are always at least half a dozen ways to complete a task in Photoshop, and that a knee-jerk reaction to pick the very latest isn’t always the best solution. It also underlines the dilemma of training new staff in a world increasingly dependent on one-stop apps. It may be convenient to just press one button and let the processor do the rest, but if you haven’t got the slightest idea what it’s doing, it’s very difficult to correct it when it goes wrong.

So it is with Photoshop’s Generative Fill and Generative Expand, which I have featured in previous columns, and are both remarkable features, but with equally deadly flaws for those who use them without carefully inspecting the results. The more you ask them to do, the more chances things will go wrong - its simple science. Adobe, however, claims that neither require technical skill as part of their campaign in creative democracy. I think that is very much wishful thinking, or rather marketing dream over practical reality.

Generative Expand is the much smarter development of Content Aware, enabling a seamless extension of an image in any direction, within limits. Eventually it runs out of things to expand without just duplicating itself, and looking fairly unconvincing. But within that limitation it does a pretty good job of replicating content in a realistic manner - including lines, patterns and shadows for example which were always a challenge for tools less smart.

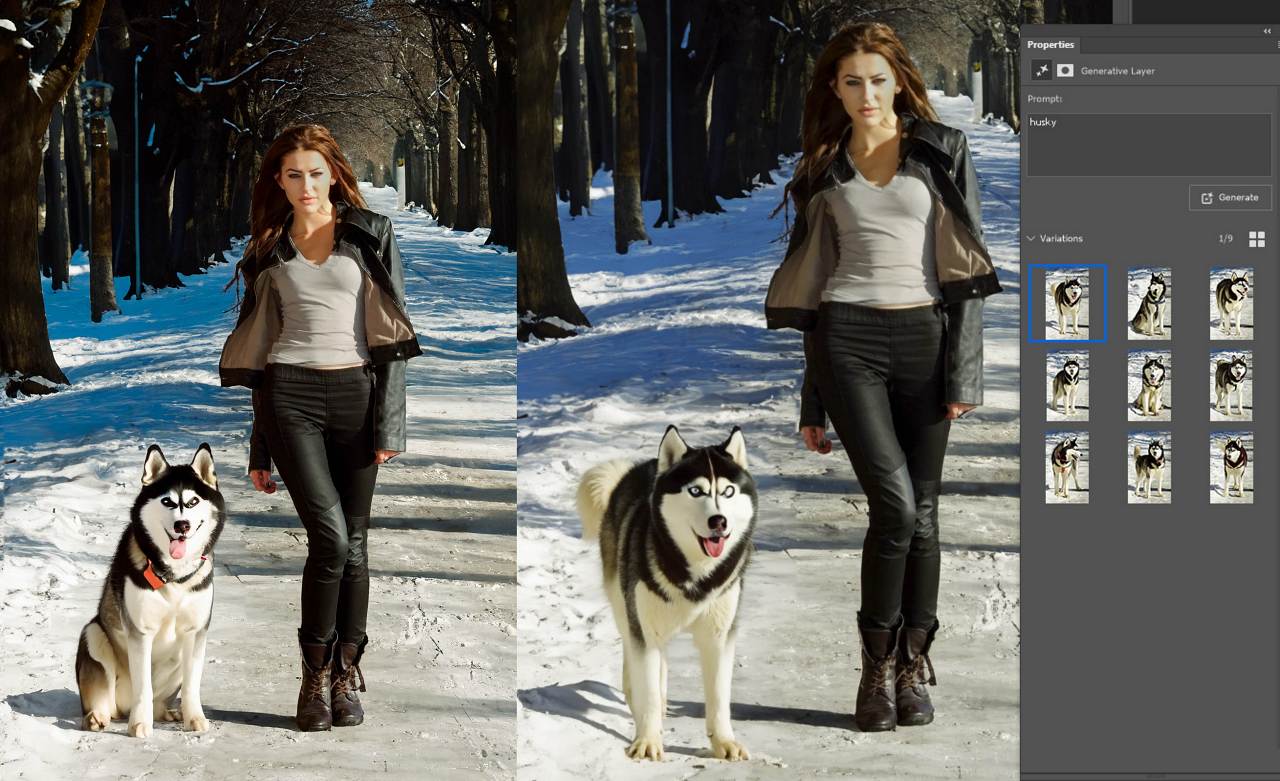

Generative Fill takes the concept much further in that as well as being able to cover a selected area in content from analysis of the original, it can also be prompted to introduce additional material from any other source available in the Adobe archives, and doctored by the instructions provided to fit in the context of that original. Original versions did suffer from a lack of resolution, but that is now improving with updates, and there is an enhance feature included in the selections.

Generative Fill takes the concept much further in that as well as being able to cover a selected area in content from analysis of the original, it can also be prompted to introduce additional material from any other source available in the Adobe archives, and doctored by the instructions provided to fit in the context of that original. Original versions did suffer from a lack of resolution, but that is now improving with updates, and there is an enhance feature included in the selections.

If you are not completely satisfied with the three options offered up, you can keep prodding it till you are happy, or just think out of the box and maybe change the wording of your original request so it better understands exactly what you want. Always remember, it’s only a machine, not a magic lantern.

Something that has been in Beta testing and may well be in the regular version of PS by the time you read this is the ability to select an image from file and use that as the fill image in a selected place. This gives more personal options if you have a number of similar images and want to introduce a feature from one into another without the clumsy and time consuming editing that would have been needed previously. So somebody could be strolling with their own dog on a lead - not a computer generated one - even if it wasn’t on walkies at the time of the photo.

Once you start thinking about the possibilities it’s a huge step forward in what can be done as long as you have something reasonable as a base to work from. The familiar answer to the question of whether you can do something on the computer is usually ‘possibly’. What you can do is still down to human judgement though customers will increasingly expect you to work miracles without incurring any cost.

The doctoring of images by the use of AI has massive implications in the wider world, but within printing we can only concern ourselves with satisfying customer demand and expectations. And our aim, as always, is to be at least one step ahead of them.

By making it easier to blend images together seamlessly, it introduces so many possibilities in the creation of what is effectively original artwork, using files already in existence, but in a different context. The area of design is a constant nightmare with customers creating something from apps on their phone, and expecting us to reproduce it professionally and suitable for print.

With Adobe you are able to call upon a vast range of files, photos, artwork and templates, which are not only high quality, but can be licensed to use commercially.

Adobe Stock is an on-line resource from which you can add files to a library on your own desktop, and has a comprehensive search engine. It’s not part of the Creative Cloud package as standard but can be added for a small monthly subscription.

If you subscribe, you accrue credits you can then use up on items you download for use, and the number of credits you spend is relative to the end use, and the licence terms required. It’s all explained in the plan detail.

As a photographer I have a large collection of images taken over a good number of years, sat on several hard drives, and randomly archived so I have a reasonable chance of finding something I’m looking for. They are also mostly my copyright so I can use them as I wish. Or if there is something I don’t have, or I need something more up to date, I can have a look through Adobe Stock to see if there is something suitable there.

Definitely worth a browse if you haven’t been there before as it opens up a whole new realm of possibilities not available to the average customer, and it is being continually updated by content from Adobe users worldwide. Some of it is already AI generated, but all of it is of a very high standard compared to other web-based libraries which most people would otherwise be directed to. It’s a lot more than a picture library.

.jpg)

.png)